2026’s Dataland and the Polarizing Preserving of AI Art

by Sebastian Flores | 12/27/25

In recent years, artificial intelligence has moved from the margins of our imaginations (think Will Smith eating spaghetti) to actually shaping how images are made, music is composed, and stories are told. Alongside this rapid adoption, has come significant resistance rooted in ethical and artistic concerns. There is a great divide between the artist/individual and the label or company when it comes to the perspectives of AI. Few developments reflect this tension more clearly than Dataland, a museum in Los Angeles set to open in 2026 dedicated entirely to art created with artificial intelligence. Its very existence signals that the art is being positioned as a legitimate and enduring artistic genre.

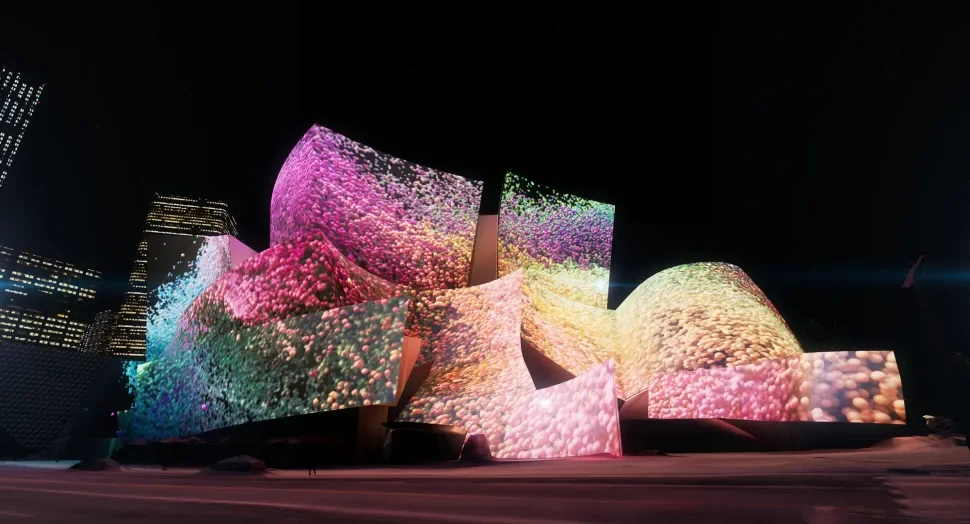

What makes Dataland particularly notable is its institutional scale and ambition. Museums have always played a powerful role in validating new forms of art, from photography to video and digital media to film. In the 1940 the Museum of Modern Art established its Department of Photography, becomign the first of its kind to include the medium. Museums such as Tate Modern and MoMA set the global standard for video art. By committing resources and a long-term vision to AI-generated and AI-assisted work, Dataland is trying to do the same, suggesting that AI is not just a tool but a medium in its own right. Under the artistic direction of figures such as Refik Anadol, the museum emphasizes hopes to reframe creativity as a collaboration between human intention and machine process.

Yet this recognition arrives amid a strong and growing resistance. Within this current environment more and more companies and studios and figureheads are turning to AI and more and more people are becoming frustrated with its shortcoming. Youtube is getting heavily criticized for its new AI driven moderation, Friend.com is getting smoked on twitter, and the biggest gripe with AI art is: that AI-generated art lacks intention or lived experience, it is unembodied creativity. There is also a clear labor anxiety: as companies adopt AI for efficiency and scale, creative workers fear being displaced and devalued, thus AI for many is actually cutting short the future of those whom it is trained upon.

At the same time, now more than ever is corporate and institutional acceptance of AI accelerating. Media companies, design firms, and entertainment studios increasingly see AI as a real, practical, and profitable tool, and cultural institutions are beginning to follow suit. Dataland sits at the intersection of these contrasting forces, offering cultural legitimacy to AI art while also inheriting the risks of commercialization. The question becomes whether such institutions can engage with the many convoluted implications of AI, or whether they will simply aestheticize technological power.

When AI first made its wave a few years ago, many hoped that it will make life easier by doing the mundane, and yet we are continuing to challenge it to do the extraordinary. If AI art is to endure, it must be shaped by ethical reflection and artistic responsibility as much as by technological capability. In this way, Dataland’s greatest value may lie in the conversations it forces us to have about creativity, authorship, and the future of art itself.